|

With the threat of enemy missile attacks on the

U.S. and our allies ever present, the need for interception

capabilities grows. To that end, the Pentagon's Ballistic

Missile Defense System has a new star player: The Kinetic

Energy Interceptor.

Killer Features:

- Ground based launcher is mobile (truck

transportable)

- Italy-based launcher could shield

Western Europe; Virginia based launcher could defend

Atlantic coast

- Top speed will be in excess of 12,000

mph

- Can be submarine launched from modified

Ohio-class SSBN submarines

The mandate of the Missile Defense

Agency (MDA) is simple: Protect America and her allies

from the threat of Theater and Intercontinental Ballistic

Missiles. Getting the job done, on the other hand, is

not quite that easy, especially in an age where enemy

missiles could be launched from conceivably anywhere.

To provide as much coverage as possible, in addition

to developing high energy systems such as the Airborne

Laser (ABL), the MDA is researching a number of ground

and sea-based approaches, one of which is a direct attack

kinetic energy interceptor (KEI). This projectile has

one purpose: Track incoming missile threats, and destroy

them with a non-explosive kinetic energy warhead.

A View to a Kill

The KEI system, as being developed by

Northrop Grumman and Raytheon on a joint contract, features

a mobile land-based launcher built by Northrop Grumman

and subcontractor SEI; a Raytheon-built interceptor

that will be faster and more agile than any other interceptor

to date; a HMMWV that will house the command and control

battle management and communications system; and satellite

receivers to process the signal that a hostile missile

has been launched. The equipment is highly mobile and

can be easily loaded onto a C-17 aircraft and transported

worldwide.

At approximately 12 meters long and

1 meter wide, the KEI interceptor is twice the size

the RIM-161A Standard Missile-3 (SM-3), which currently

provides allied forces and U.S. protection from short

to intermediate range ballistic missiles. The KEI attacks

its targets at a maximum speed of 12,000 mph, more than

twice the speed of the SM-3. Its premise is logical:

destroy enemy missiles in their most vulnerable stage

-- the "boost" phase of flight, before reentry

vehicles, decoys or countermeasures can be deployed.

|

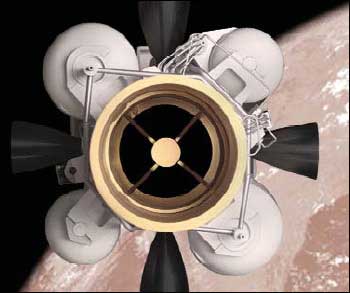

| In

for the kill: The Exoatmospheric Kill Vehicle within

the KEI projectile seeks out and demolishes enemy

missiles. |

When a threat has been detected, the

KEI projectile is launched toward its target. The first

and second stages of the booster will burn together

in 60 seconds, giving the projectile a speed of 6 kilometers

per second. Finally, the projectile adjusts its trajectory

and ejects the Exoatmospheric Kill Vehicle, a device

that is used to destroy enemy missiles outside the atmosphere.

The Kill Vehicle uses an infrared seeker to detect and

discriminate the reentry vehicle from other objects.

Then the "hit-to-kill" concept is carried

out, as the Kill Vehicle collides with the incoming

warhead, completely pulverizing it.

Larger Engagement Area

The challenges involved in the KEI program

are manifold. In order to catch the missiles it is supposed

to destroy, the KEI needs to be fast -- really, really

fast. This is accomplished by making the KEI small and

light and packing it with solid rocket fuel. Unfortunately,

the tradeoff is that by doing so you limit the missile

to "boost" phase interceptions. For most theater

missiles, this is around 3 minutes (180 seconds), not

a very large launch window.

Due to this, the defending KEI battery

was initially intended to be stationed relatively close

to enemy threat launch platforms (500-1,500 km), which

would cut down on their effectiveness against missiles

launched from countries with large land masses, such

as Iran and China, or from blue-water launches from

open ocean. On the other hand, target missile tracking

during the boost phase is easier, since the missile

is accelerating linearly, and decoys, such as flares

and chaff bundles, would be less effective.

So it looked as KEI would be locked

down in its "boost phase" role, but conditions

change. But MDA's decision to build a highly flexible

kill vehicle for the KEI - which would be effective

in other phases of the missile defense regime - helped

convince agency officials that the missile could be

a capable performer in the ascent and mid-course phases

of a missile attack.

|

| Photo

of the KEI Launcher. |

Upgrading the KEI to a "mid-course"

interceptor would enlarge the KEI's engagement window

considerably. During the mid-course phase, the threat

missile is no longer accelerating, and is arcing ballistically

through its apogee towards the target. This phase can

last as long as 1200 seconds, which would give an "assent"

or "mid-course" capable KEI 20 minutes to

engage the target.

It all adds up to a large engagement

area for the KEI. For example, a single battery of 10

missiles based in Italy could protect all of western

Europe against Middle East missile threats. One battery

based in Norfolk, Va., could protect the East Coast

of the United States from a launch 300 to 1,500 kilometers

off the coast. This is in opposition to KEI's critics,

who have stated that the weapon is essentially a one-country

missile intended to defend against an attack by North

Korea.

Challenges Ahead

One caveat to the "mid-course"

approach is that the missile would need to be significantly

larger than the current 12 meters long and 1 meter wide.

While this is not an issue for sub-launched, or ground-based

interceptors, the size makes their use aboard guided

missile cruisers and destroyers problematic (the largest

missile currently launched from the Ticonderoga cruisers

and Arleigh Burke destroyers is the SM-3 missile, which

is 6.5 meters long, and has a finspan of 1.5 meters.

|

| KEI

Command Center: C2BMC Shelter with Interceptor Communication

Antenna. |

Another challenge facing the KEI is

actually hitting the target. While anti aircraft missile

interception technology has been around for some 40

years, the precision needed to intercept a ballistic

missile is significantly higher. The greatest challenge

in this equation is the data processing limitations

in the guidance system. With a closing speed as high

as 37,000 meters per hour (22,000 miles per hour), a

target missile can literally move hundreds of feet between

the computational cycles of the interceptor's course

correction software. As if that wasn't enough, the engagement

solution can be further complicated by the use of decoys,

such as flares and chaff, to spoof the KEI's sensors

and have it attack the wrong target.

"If it's an elaborate countermeasure,

then we will have to get more sophisticated," says

Larry Little, program director of the Missile Defense

Agency's KEI office. Getting around this problem could

be accomplished with smaller, terminally launched seeker

warheads, carried aloft by a booster, which would attack

all targets in the missile path, rather than try and

discriminate between target and decoy. Still another

option is to adopt a different tactic. "You don't

necessarily discriminate, you just shoot everything

that is up there," Little said.

Despite these challenges, a Northrop-Grumman/Raytheon

team is confident that they can meet the goals set by

the MDA. Granted $4 billion over the next 8 years, the

team is developing a "multi-window" KEI missile

using technology developed for the fielded SM-3 missile

interceptor. They are expected to have a prototype Ground

launched system ready for evaluation by 2010, with a

sea-based system ready by 2013. Initial elements of

the missile defense system, comprising two destroyers

armed with SM-3 air defense missiles, are to be deployed

in September. |